A few months ago, one of our bloggers, the “backstage sociologist” Monte Bute offered up a post that referenced political theorist Isaiah Berlin’s famous distinction between foxes and hedgehogs. In the world of ideas, according to Berlin (borrowing from ancient Greek poet Archilochus), there are those who know many, many things (foxes), and those who know one big thing (hedgehogs). Berlin’s categories have been widely referenced in both the social sciences and the humanities to identify styles of thought, the contributions of various scholars, and lines of research and writing. In reflecting on Berlin’s categories back in the long, lazy days of summer, Chris and I had a little fun putting our favorite sociologists and works in one box or the other. And as we played with the categories and thought about sociology as a discipline, we began to realize anew—much as I think Berlin meant to suggest (this appeared in an essay about Tolstoy)—that real insight and understanding in any field requires both foxes and hedgehogs.

A few months ago, one of our bloggers, the “backstage sociologist” Monte Bute offered up a post that referenced political theorist Isaiah Berlin’s famous distinction between foxes and hedgehogs. In the world of ideas, according to Berlin (borrowing from ancient Greek poet Archilochus), there are those who know many, many things (foxes), and those who know one big thing (hedgehogs). Berlin’s categories have been widely referenced in both the social sciences and the humanities to identify styles of thought, the contributions of various scholars, and lines of research and writing. In reflecting on Berlin’s categories back in the long, lazy days of summer, Chris and I had a little fun putting our favorite sociologists and works in one box or the other. And as we played with the categories and thought about sociology as a discipline, we began to realize anew—much as I think Berlin meant to suggest (this appeared in an essay about Tolstoy)—that real insight and understanding in any field requires both foxes and hedgehogs.

Certainly sociology fits this characterization. The foxes among us collect tons of data and generate myriad facts and explanations of facts, and our hedgehogs work tirelessly to organize these ideas and information in big conceptual frames, organizing theories, and frameworks. Yet the more Chris and I talked and thought, the more we found ourselves uncomfortable with the dualistic distinction: the scholars and works we like best didn’t quite fit into the boxes. Further, the usual ways of thinking about the relationships between foxes and hedgehogs (either privileging one over the other or thinking of each as balancing the other, contributing equally in its own way) didn’t seem to capture what is truly unique, important, and inspiring about sociology as a intellectual pursuit.

We think about sociology not as a competition between foxes and hedgehogs, nor even as a balancing act between these different styles of thought, but as a genuine, ongoing synthesis of these approaches. Sociologists are necessarily engaged in both fox- and hedgehog-like thinking, operating at different levels, up and down and all around the social world.

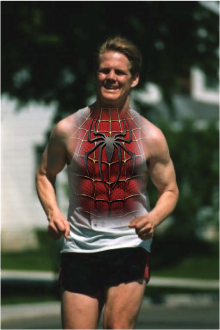

Chris went back into his early graduate school theory days and suggested that the imagery of a different creature—a spider—better captured the essence of the sociological enterprise (an idea adapted from a Francis Bacon essay Chris once read for class). The spider doesn’t so much think about one big thing or lots of smaller things, but does both at once. Put differently, the spider is oriented toward weaving all of the little strings into a grand, synthetic whole.

I felt a bit like that synthetic spider this past weekend when I spoke at a big immigration event at the faith-based community—okay, it’s a Lutheran Church—with which I have long been affiliated in the Twin Cities. The event was less about immigration reform than about welcoming immigrants in our communities. We discussed how individuals and organizations, neighborhoods, and entire cities can do a better job of understanding, engaging, and integrating societal newcomers and outsiders more generally. I was asked to give the main, initial framing talk. Consistent with my vision of the value of social scientific information and perspective, I tried to provide some basic facts, important context, and useful concepts about immigrants, migrants, and immigration in the contemporary United States. I talked about about immigrants and foreign-born people in the U.S. and around the world; recent research on attitudes about immigration, immigrants, and immigration reform; patterns of assimilation and incorporation of recent immigrants and their children; and a brief overview of economic costs and benefits of migration and movement. Most of this research was drawn from others in the field. In fact, some in the audience were undoubtedly more expert and informed on some of these issues and aspects than I. But as a sociologist, I was well positioned to pull all of this information and ideas together and present them in a format that was as (relatively) engaging and accessible as it was informative. And from the feedback I received (and how well the rest of the event went), I think these ideas and information provided a fairly useful frame for thinking and interacting: a web within which we could all operate.

We sociologists find ourselves doing such web-spinning all the time, at different levels, and through a range of media—community groups, classrooms, talks and presentations, blog posts, newspaper op-eds, media interviews, and, of course, on TSP, especially with our extended features and white papers. Probably our most famous and most successful example came early this fall when my partner and collaborator, Chris, was asked to be part of a White House event on some of the collateral consequences of our current punishment and prison policies. A range of scholars and intellectuals presented findings and analyses at the event, which Chris described in a post last week, modestly titled “TSP at the White House.” But what I wanted to highlight here is that our guy was assigned the quintessential “sociological spider” role of pulling this all together, on the fly and in a lively, engaging, and informative manner. TSP couldn’t have been prouder.